2 Aristotle

2.1 Aristotelian stories

I do not want to use the term "story" in the everyday sense: one

telling, one or many listening - what is being told and listened to is a

story. Instead I want to broaden the concept like this: anything that

unfolds itself over time is a story. There are things that you can

instantly understand, and or be aware of; similarly there are some

things that only unfold over time. Story line is essentially something

that needs to take some time in order to be understood. One perceives

them in time like navigational paths, which can be interpreted in terms

of Aristotelian notions of ontological causes, story line and structure

of drama.

I do not want to use the term "story" in the everyday sense: one

telling, one or many listening - what is being told and listened to is a

story. Instead I want to broaden the concept like this: anything that

unfolds itself over time is a story. There are things that you can

instantly understand, and or be aware of; similarly there are some

things that only unfold over time. Story line is essentially something

that needs to take some time in order to be understood. One perceives

them in time like navigational paths, which can be interpreted in terms

of Aristotelian notions of ontological causes, story line and structure

of drama.

Picture 9: Any story model can serve as a tool both in analysing,

synthesising and producing structures over time.

In algorithmic design I used to promote strategy of dividing any

programming problem into begin-middle-end sequence. Recursive

application of the strategy worked out as program refinement. I called

this format "The Japanese Model" because it is simple and you can apply

it flexibly to any sequential structure.

In algorithmic design I used to promote strategy of dividing any

programming problem into begin-middle-end sequence. Recursive

application of the strategy worked out as program refinement. I called

this format "The Japanese Model" because it is simple and you can apply

it flexibly to any sequential structure.

Hollywoodian movie format is based and built on Aristotelian tragedy and

classic short-story. In this type the story is largely related trough

the fates and fortunes of main character (Aristotle).

Hollywoodian movie format is based and built on Aristotelian tragedy and

classic short-story. In this type the story is largely related trough

the fates and fortunes of main character (Aristotle).

The brechtian model, where play is a succession of independent acts,

that are joined by narrative commentary of songs and visuals (Brecht).

As a fourth example of story formulae are algorithmic outlines either

for computer programs or work and job descriptions. They have a start

and they usually have an end point. The action of algorithm is

described precisely in steps leading to the desired result. There may be

repetitions or alternative routes in the flow of algorithm but it is

essentially like a story unfolding over time.

The brechtian model, where play is a succession of independent acts,

that are joined by narrative commentary of songs and visuals (Brecht).

As a fourth example of story formulae are algorithmic outlines either

for computer programs or work and job descriptions. They have a start

and they usually have an end point. The action of algorithm is

described precisely in steps leading to the desired result. There may be

repetitions or alternative routes in the flow of algorithm but it is

essentially like a story unfolding over time.

When doing hypermedia you are working on and with computers and the end

product will be viewed on computers, so inevitably you will end up

dealing with programing and algorithms, or somebody in your group will.

The idea is that story model for hypermedia storyboarding should be

applied to algorithmic design too.

When doing hypermedia you are working on and with computers and the end

product will be viewed on computers, so inevitably you will end up

dealing with programing and algorithms, or somebody in your group will.

The idea is that story model for hypermedia storyboarding should be

applied to algorithmic design too.

2.2 Navigational paths

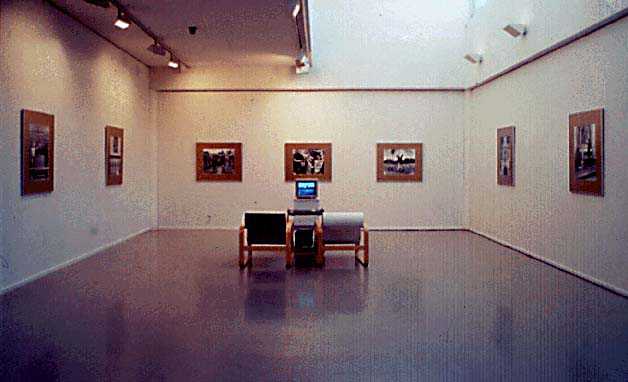

We made in spring 1994 together with photographer Jari Arffman three

installations of an interactive piece "Crusade". We had seven grayscale

photographs and three screenfuls of highly abstract text which were

interlinked for audience exploration on a Macintosh with a mouse.

Extracts of poetry read by actors were added to enrich the links. The

idea was that the exhibition visitor could look at the high quality

photographic prints and then he could, in a very postmodern manner,

deprive images of their visual meaning and start exploring them in

association with a very conceptual text framework.

We made in spring 1994 together with photographer Jari Arffman three

installations of an interactive piece "Crusade". We had seven grayscale

photographs and three screenfuls of highly abstract text which were

interlinked for audience exploration on a Macintosh with a mouse.

Extracts of poetry read by actors were added to enrich the links. The

idea was that the exhibition visitor could look at the high quality

photographic prints and then he could, in a very postmodern manner,

deprive images of their visual meaning and start exploring them in

association with a very conceptual text framework.

Picture 10: Crusade installation in Alvar Aalto museum in Jyväskylä,

Summer -94.

We wanted to have a few people at a time engaged in exploring images and

the text preferably engaged in mutual conversation. We did not put in

any navigational clues, because contemplation over our material through

free exploration was one of the points of our piece. To get those minds

moving and the conversation going. I wanted to leave it to the dark

attractors of chaos in the work to make and keep audience interested.

We wanted to have a few people at a time engaged in exploring images and

the text preferably engaged in mutual conversation. We did not put in

any navigational clues, because contemplation over our material through

free exploration was one of the points of our piece. To get those minds

moving and the conversation going. I wanted to leave it to the dark

attractors of chaos in the work to make and keep audience interested.

I call this form of hypermedia hyperpoetry, because it thins out the

narrative and does not necessarily have story lines as such. At best

this leads to contemplative interaction between the explorer and work

and is an attempt in lyrical hypermedia expression.

I call this form of hypermedia hyperpoetry, because it thins out the

narrative and does not necessarily have story lines as such. At best

this leads to contemplative interaction between the explorer and work

and is an attempt in lyrical hypermedia expression.

I was very happy to see and learn later on that roughly about a third of

the visitors were pleased with the experience. They said it was

something adding to the images on the wall. Of course, one third said it

was completely beyond their understanding. Perhaps that evens the

success out a bit. This was our crusade into a storyless composition -

conclusion was that the lack of narration personalises the experience -

not so much diminishing it but rather rendering it incommunicable

further.

I was very happy to see and learn later on that roughly about a third of

the visitors were pleased with the experience. They said it was

something adding to the images on the wall. Of course, one third said it

was completely beyond their understanding. Perhaps that evens the

success out a bit. This was our crusade into a storyless composition -

conclusion was that the lack of narration personalises the experience -

not so much diminishing it but rather rendering it incommunicable

further.

A navigational path lays out a story, the flow of which can be

user-controlled, marked by attractors, outlined by agents or led by a

guide. Crusade took the user control to the extreme offering no cues and

no stories. A navigational path can be marked out for the user by icons

that connote the line of narration.

A navigational path lays out a story, the flow of which can be

user-controlled, marked by attractors, outlined by agents or led by a

guide. Crusade took the user control to the extreme offering no cues and

no stories. A navigational path can be marked out for the user by icons

that connote the line of narration.

An agent can be represented by anything - in hypermedia documents it

means that any programmable object can call up operations that complete

the task of called agent. In modest environments text labels and icons

can represent agents.

An agent can be represented by anything - in hypermedia documents it

means that any programmable object can call up operations that complete

the task of called agent. In modest environments text labels and icons

can represent agents.

One term has been coined: knowbots - software robots, task performers,

programmed entities that exist only inside the computer. They may have

some defined task-handling skills, even learning skills and so on.

One term has been coined: knowbots - software robots, task performers,

programmed entities that exist only inside the computer. They may have

some defined task-handling skills, even learning skills and so on.

A primitive example of an agent controlling any arbitrary linear story

could be a leafer agent that is implemented essentially as two routines

that use an index - a list of is-a-kind-of components in their

navigating order. The two routines locate the name of the component the

navigator is at from the index and according to the call either choose

the name above or below it and take the navigator there. In our first

experiment, Codex B, the hypernovel we placed these routines into an

animated icon of a book that leafed itself back and forth and took the

navigator back and forth in our stories. I know that this is stretching

the agent concept, but the rationale was to offer a context free service

(an agent) that anyone would intuitively be able to use. This

arrangement also enabled us to modify and rearrange the stories freely

once we kept the index in order.

A primitive example of an agent controlling any arbitrary linear story

could be a leafer agent that is implemented essentially as two routines

that use an index - a list of is-a-kind-of components in their

navigating order. The two routines locate the name of the component the

navigator is at from the index and according to the call either choose

the name above or below it and take the navigator there. In our first

experiment, Codex B, the hypernovel we placed these routines into an

animated icon of a book that leafed itself back and forth and took the

navigator back and forth in our stories. I know that this is stretching

the agent concept, but the rationale was to offer a context free service

(an agent) that anyone would intuitively be able to use. This

arrangement also enabled us to modify and rearrange the stories freely

once we kept the index in order.

Similarly it is relatively easy to construct services that select items

or indexes or both. With the selection method they can impose their

intentions on the navigator, and as such assume the role of a narrator

or instructor. Use of agents, especially intelligent agents or agencies

(collections of agents) in storytelling - laying out navigational paths

- is definitely one of the main techniques in future hypermedia.

Similarly it is relatively easy to construct services that select items

or indexes or both. With the selection method they can impose their

intentions on the navigator, and as such assume the role of a narrator

or instructor. Use of agents, especially intelligent agents or agencies

(collections of agents) in storytelling - laying out navigational paths

- is definitely one of the main techniques in future hypermedia.

Through artificial intelligence techniques you can device intelligent

entities that represent or draw your story line, who are guardians of

your story, or they tell or act you the story. I have often called

agents with distinct intentions guides - one example might be learning

companions in educational titles. More about agents in (Maes) or

(Minsky), Apple Computer's Guide -project is discussed in (Laurel 90).

Through artificial intelligence techniques you can device intelligent

entities that represent or draw your story line, who are guardians of

your story, or they tell or act you the story. I have often called

agents with distinct intentions guides - one example might be learning

companions in educational titles. More about agents in (Maes) or

(Minsky), Apple Computer's Guide -project is discussed in (Laurel 90).

2.3 Aristotle's four causes

Aristotle uses a metaphor of a chair making when he explains his ideas

of the four causes of all existence. Same ontological principles apply

in and on all design levels, I will elaborate this on story's

is-a-kind-of components.

Aristotle uses a metaphor of a chair making when he explains his ideas

of the four causes of all existence. Same ontological principles apply

in and on all design levels, I will elaborate this on story's

is-a-kind-of components.

Formal cause: There is a form of chair, a universal chair form that all

chairs wish to fulfil. A table does not fulfil the form of chair, so

nobody calls it a chair.

Formal cause: There is a form of chair, a universal chair form that all

chairs wish to fulfil. A table does not fulfil the form of chair, so

nobody calls it a chair.

Material cause: The matter out of which the chair is made sets

constraints to its properties. It makes a difference if the chair is a

wooden or a metal one.

Material cause: The matter out of which the chair is made sets

constraints to its properties. It makes a difference if the chair is a

wooden or a metal one.

Efficient cause: Aristotle means by them the skills and the tools

available for the chair maker.

Efficient cause: Aristotle means by them the skills and the tools

available for the chair maker.

End cause: Not least even if last, the end cause. Why chairs? For

princes or paupers?

End cause: Not least even if last, the end cause. Why chairs? For

princes or paupers?

Let us apply these principles in hyperboarding: With formal cause I mean

that there are certain ways (data formats for the items) you need or

have to represent certain is-part-of contexts. One has to be aware of

what one is describing in writing - basic linear text, dialogue,

something one needs to represent visually or with simulations. Certain

messages and statements crave certain forms of expression. Also some of

the formats (videoclips) are overappreciated and others underrated

(animation).

Let us apply these principles in hyperboarding: With formal cause I mean

that there are certain ways (data formats for the items) you need or

have to represent certain is-part-of contexts. One has to be aware of

what one is describing in writing - basic linear text, dialogue,

something one needs to represent visually or with simulations. Certain

messages and statements crave certain forms of expression. Also some of

the formats (videoclips) are overappreciated and others underrated

(animation).

Material cause is the physical data that hyperdocument incorporates. At

first most of it is described in writing that evolves towards the end

layout and representations gradually throughout the project. One might

say that text is the stuff hypermedia is made of and it follows that

hyperboarding is writing hypertext for the hypermedia application. As

the design progresses and better understanding of size and media

constraints is achieved, decisions on the number, size, binary type of

the composite data elements are made.

Material cause is the physical data that hyperdocument incorporates. At

first most of it is described in writing that evolves towards the end

layout and representations gradually throughout the project. One might

say that text is the stuff hypermedia is made of and it follows that

hyperboarding is writing hypertext for the hypermedia application. As

the design progresses and better understanding of size and media

constraints is achieved, decisions on the number, size, binary type of

the composite data elements are made.

Efficient cause means the tools and know-how. When one is embarking on a

hypermedia project one has to analyse the possible audience, its size,

the variety of its computers. Then one has to make allowances for what

machines and environments one really has at hand in the production

phase etc. The skills and methodologies one acquires and accumulates

during the project may have great influenece on the end title. The

efficient cause working on one's title is something you cannot really

fix to any given time. The process and equipment develops so fast that

you may want to keep your design very modifiable at this point in order

to take advantage of technological development. The development of both

job and task routines and skills together with group work dynamics and

tools is vital in securing quality and timing in all hypermedia

projects.

Efficient cause means the tools and know-how. When one is embarking on a

hypermedia project one has to analyse the possible audience, its size,

the variety of its computers. Then one has to make allowances for what

machines and environments one really has at hand in the production

phase etc. The skills and methodologies one acquires and accumulates

during the project may have great influenece on the end title. The

efficient cause working on one's title is something you cannot really

fix to any given time. The process and equipment develops so fast that

you may want to keep your design very modifiable at this point in order

to take advantage of technological development. The development of both

job and task routines and skills together with group work dynamics and

tools is vital in securing quality and timing in all hypermedia

projects.

End cause - the reason. The principal constraint one needs to impose on

one's work is the message or collection of messages you want to convey

to the navigator. This is best formulated in a couple of concrete and

descriptive sentences. This definition serves as the ultimate measure in

deciding which design propositions are accepted and which rejected,

therefore it is utterly important that the team agrees and understands

the document's purpose - its end cause.

End cause - the reason. The principal constraint one needs to impose on

one's work is the message or collection of messages you want to convey

to the navigator. This is best formulated in a couple of concrete and

descriptive sentences. This definition serves as the ultimate measure in

deciding which design propositions are accepted and which rejected,

therefore it is utterly important that the team agrees and understands

the document's purpose - its end cause.

2.4 Tableau

Next I will break stories into components that can simultaneously belong

to a number of stories. A story is a sequence of tableaux that are in an

is-a-kind-of relation to each other. One is going from one screen to

another when one navigates through a hypermedia title. The screens frame

out the document for you in tableau by tableau. Our national poet

Aleksis Kivi uses word "asuma", when he goes out in the summer by a lake

and gazes at the sunset and what he sees, hears, smells and feels he

calls asuma: a moment of stillness, something that one can stand and

take a look at, understand and contemplate. For Finns there are

connotations of "asuma" - to live, habitus, attire, inhabit, home. My

idea is that a tableau should not be conceived unfolding over time but

something that can be grasped instantly as a whole.

Next I will break stories into components that can simultaneously belong

to a number of stories. A story is a sequence of tableaux that are in an

is-a-kind-of relation to each other. One is going from one screen to

another when one navigates through a hypermedia title. The screens frame

out the document for you in tableau by tableau. Our national poet

Aleksis Kivi uses word "asuma", when he goes out in the summer by a lake

and gazes at the sunset and what he sees, hears, smells and feels he

calls asuma: a moment of stillness, something that one can stand and

take a look at, understand and contemplate. For Finns there are

connotations of "asuma" - to live, habitus, attire, inhabit, home. My

idea is that a tableau should not be conceived unfolding over time but

something that can be grasped instantly as a whole.

We all know that aesthetic appreciation sometimes requires training,

education, understanding, experience and so on. It stands to reason that

some people understand some wholes (and tableaux) more readily than

others. When we enter a room we instinctively conceive it as a unit 'X's

room, Y's office etc.' - our knowledge of the content changes as we

visit the room more often - but it still is understood as some one

thing.

We all know that aesthetic appreciation sometimes requires training,

education, understanding, experience and so on. It stands to reason that

some people understand some wholes (and tableaux) more readily than

others. When we enter a room we instinctively conceive it as a unit 'X's

room, Y's office etc.' - our knowledge of the content changes as we

visit the room more often - but it still is understood as some one

thing.

Concrete realisation of a tableau may be a layout, just a simple

newspaper page, for instance, it can be an ideal tableau for joining

several story lines. Or it may be a painting, a still life, or it can be

any collection - a collection of things. A snapshot of me lecturing at

the podium here counts for a tableau. Situation... a pose, a scene - we

approach drama and film.

Concrete realisation of a tableau may be a layout, just a simple

newspaper page, for instance, it can be an ideal tableau for joining

several story lines. Or it may be a painting, a still life, or it can be

any collection - a collection of things. A snapshot of me lecturing at

the podium here counts for a tableau. Situation... a pose, a scene - we

approach drama and film.

Wittgenstein in his "Tractatus Logicus Philosophicus" offers a formal

view to tableau as he explains how facts are comprised of states of

affairs. He sees behind linguistic concepts that can be understood as

facts bundles of facts that are connected by grammars (Wittgenstein).

One combination of facts produces a new fact and further on another

combination (to another level of abstraction). Wittgenstein is very

useful when you deal with computers and computer programming because he

says you should shut up if you do not know what to say, which is

precisely what you have to do with computers. Wittgenstein's "Tractatus

Logicus Philosophicus" is a very useful piece of philosophy if you are

dealing with computer programming, program design or algorithmic design.

Wittgenstein in his "Tractatus Logicus Philosophicus" offers a formal

view to tableau as he explains how facts are comprised of states of

affairs. He sees behind linguistic concepts that can be understood as

facts bundles of facts that are connected by grammars (Wittgenstein).

One combination of facts produces a new fact and further on another

combination (to another level of abstraction). Wittgenstein is very

useful when you deal with computers and computer programming because he

says you should shut up if you do not know what to say, which is

precisely what you have to do with computers. Wittgenstein's "Tractatus

Logicus Philosophicus" is a very useful piece of philosophy if you are

dealing with computer programming, program design or algorithmic design.

2.5 Aristotle revisited

I will apply Aristotle's ontological principles on tableau description:

in hyperdocument one has a number of stories that are comprised of

tableaux. One starts hyperboarding by outlinig one's stories - and it is

very advisable to use several authors, so one gets the personal flair to

each story. As a team you decide and work on the tableaux that are

shared by individual stories. The process shifts between your own desks

and meetings where you refine the tableaux for your stories. It is

useful to start describing tableaux in terms of the end cause. Define

the meaning, the fact you want the navigator to grasp instantly. A short

and precise definition of its purpose and/or aim - for the team it is

also a goal. Because you are working in a team, you have to make

compromises, you have to make common decisions on what ideas go in and

what is left out. The end cause serves as the measurement in making

those decisions. It is vital that one does that definition otherwise one

ends up having horrible arguments with nothing getting done at some

point in the project.

I will apply Aristotle's ontological principles on tableau description:

in hyperdocument one has a number of stories that are comprised of

tableaux. One starts hyperboarding by outlinig one's stories - and it is

very advisable to use several authors, so one gets the personal flair to

each story. As a team you decide and work on the tableaux that are

shared by individual stories. The process shifts between your own desks

and meetings where you refine the tableaux for your stories. It is

useful to start describing tableaux in terms of the end cause. Define

the meaning, the fact you want the navigator to grasp instantly. A short

and precise definition of its purpose and/or aim - for the team it is

also a goal. Because you are working in a team, you have to make

compromises, you have to make common decisions on what ideas go in and

what is left out. The end cause serves as the measurement in making

those decisions. It is vital that one does that definition otherwise one

ends up having horrible arguments with nothing getting done at some

point in the project.

And then the material cause. By and large this means the text.

Description of the content of tableau in text format gives the authors a

better understanding to the quality, quantity and scope of information

desired. This is the basis of its material cause, the substance of our

end title. The text may be decomposed into several items.

And then the material cause. By and large this means the text.

Description of the content of tableau in text format gives the authors a

better understanding to the quality, quantity and scope of information

desired. This is the basis of its material cause, the substance of our

end title. The text may be decomposed into several items.

Picture 11: A template for tableau description

The formal cause defines the vessels (dataformats) for realising the

content. By that I mean that the left column (picture 11) contains the

material - e.g. a piece of dialogue - as its formal cause one defines

in the right column correspondingly "how one does it", e.g. "Two icons

having a dialogue in text fields, so as to give a 'semi-animated comic

strip' effect". Formal cause is how one chooses to define the way one is

going to do it when one gets the equipment and the time etc., etc...

Even if one cannot go into details yet, the important thing is that one

tries to describe the corresponding format for every text-item in the

material cause. Then one analyses, synthesizes and produces the final

tableau filtered by the efficient cause.

The formal cause defines the vessels (dataformats) for realising the

content. By that I mean that the left column (picture 11) contains the

material - e.g. a piece of dialogue - as its formal cause one defines

in the right column correspondingly "how one does it", e.g. "Two icons

having a dialogue in text fields, so as to give a 'semi-animated comic

strip' effect". Formal cause is how one chooses to define the way one is

going to do it when one gets the equipment and the time etc., etc...

Even if one cannot go into details yet, the important thing is that one

tries to describe the corresponding format for every text-item in the

material cause. Then one analyses, synthesizes and produces the final

tableau filtered by the efficient cause.

For an efficient cause one needs to analyse what is feasible and lay

down a production schedule and DO IT. This means the tools, facilities,

skills, personnel and time available for the final tableau from the

production point of view. In order to understand the effects and

efficiencies shaping your work you need to have an understanding of your

audience and the equipment available to them. It may even be reasonable

to invest project money in improving infrastructure (network

organisation or database management) rather than producing a single

glamorous hyperdocument.

For an efficient cause one needs to analyse what is feasible and lay

down a production schedule and DO IT. This means the tools, facilities,

skills, personnel and time available for the final tableau from the

production point of view. In order to understand the effects and

efficiencies shaping your work you need to have an understanding of your

audience and the equipment available to them. It may even be reasonable

to invest project money in improving infrastructure (network

organisation or database management) rather than producing a single

glamorous hyperdocument.